Charting Science Writing

Posted: April 28, 2013 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: charts, exemplars, science, vocabulary 12 CommentsWe have received many requests from teachers looking for ways to use charts that reinforce their teaching of information writing, so when Katie Wears, a staff developer at the Reading and Writing Project, shared with us some photos of science writing charts her teachers at Kiel Elementary School in Kinnelon, New Jersey had made during their “Writing Like Scientists” unit, we immediately asked if they would share their process with all of us at here at Chartchums. They generously agreed and the following guest blog post is the result. Our thanks to Liz Mason, first grade teacher, Jenna McMahon and Nicole Gillette, second grade co-teachers, and to Katie Wears for bringing us all together!

We are honored to be contributing to Chartchums; a place where educators from all over come to collaborate and be inspired by Marjorie, Kristi, teachers, and the students they work with. Thank you for letting us share some of the things we have been working on.

When spring arrived, the teachers at Kiel Elementary School were excited to think more about science and science writing. We planned with each other and brainstormed many possibilities for the science units and how to inspire science writing and thinking. Currently, First Grade is finishing up their study of Properties of Matter and Second Grade is studying Forces and Motion.

One goal was to help students better understand the scientific process and be able to feel successful with this “new” kind of writing. We created these two charts to provide a scaffold for the students and to support independence with the scientific process and writing about science.

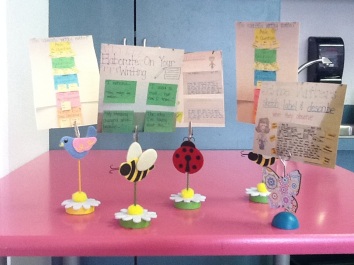

Exemplars were created to give the young scientists a vision of how their writing could go. This chart was created to support students with the procedure part of the lab report. It was exciting to see the children discuss the things they noticed in the exemplars and put those things into their own lab reports. The children were eager to use the exemplars as models for their own writing, to set goals, and to become independent. Young scientists looked at their own writing alongside the exemplars and used the exemplars to give their partners “stars” and “wishes” or compliments and tips.

Here are some other exemplars that were created during the first part of our units.

Another goal of this unit was to increase academic vocabulary. These charts and tools give students the vocabulary they need to share their learning and thinking during discussions and through their writing. The vocabulary was introduced and reinforced through real alouds, shared reading, video clips, experiments and writing. The young scientists use these charts to show everything they know.

We also wanted the young scientists to be able to use writing and the scientific process to be able to deepen their understanding and thinking. Scientists analyzed their results to draw conclusions and share their thinking. The writing on this chart was done with Jenna’s second grade class during shared writing. The chart was then created during writing minilessons when Jenna and Nicole were teaching students how to develop their conclusions and revise their thinking. They give students a model of how to share their learning through their writing.

Small versions of the charts were made and are available for the young scientists to use.

The young scientists are now using these charts and tools to support each other and work collaboratively in science clubs. In their clubs they make decisions, have different roles, formulate questions, and go through the process of gathering the materials to conduct experiments.

The prompts on the charts guide the students and help them have more meaningful scientific conversations about their learning and discoveries. As a result, each student has developed an identity as a scientist who is curious about the world and knows how to search for answers and share scientific results and thinking with others.

Best of luck,

Liz, Jenna, Nicole, and Katie

Charting Poetry Part 2

Posted: April 14, 2013 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: free verse, genre, images, mentors, poetry 2 CommentsHello Poets!

As National Poetry Month continues, so does our classroom work around it. Kristine’s kindergarten is hard at work creating original works of staggering genius 🙂 ie, poetry. Poetry can be tricky work for children when too many rules are placed around it, so with inspiration from published poets like Zoe Ryder White (find more about her here) and Valerie Worth (All the Small Poems and Fourteen More), this class decided to go with free verse around topics that were important to them, and ultimately important to all young children.

As with any unit, the study began with understanding the genre, in this case what IS a poem and what ISN’T, which also helps to define expectations for children. Given the amount and variety of poetry that children have been exposed to, it was difficult to nail down specifically what separates poetry from not poetry. In the end the class decided it was really just that stories have words that go all the way across the page, and poems don’t.

Note that the heading is in the form of a question. Next there is a prompt to find out some possible answers. The T-chart underscores the points to consider.

After this introductory lesson, the children went off to write so Kristine could get a baseline assessment of what students needed to work on in this unit. Kindergarten writing can sometimes feel like every unit has the same goal: write and draw with meaning and more readability, however, poetry has something special to add – creating lasting images and seeing the world in new ways. We were fortunate to have Zoe Ryder White come into our school early in our unit to talk with children about seeing with “poet’s eyes.”

Zoe first read a poem she had written that looked at the moon in a new way. Then she brought out a bag of ordinary objects and the class co-constructed a list poem (a poem where all the lines relate back to one idea- usually the title) about one object: a pine cone. Zoe asked the students again and again to look past the obvious and imagine more about the simple object. When Zoe and Kristine spoke afterwards, Zoe pointed out this imagining is no different than the imaginary play we value so much in the primary grades. The ability to look at a block of wood and use it as a telephone accesses the same skill set as seeing with poet’s eyes. It struck Kristi that the lessons she was doing around this for poetry would be a perfect cross over for choice time and vice versa.

After the students had been writing and reading (in shared reading and read aloud poems) Kristi kept an eye out for children trying things out that they had seen in these mentor texts. She used these in her shares and minilessons to create a strategy chart of poetic devices.

Whenever crafting charts, it is helpful to find student examples since the children are all within a similar zone of proximal development. Mentor texts do not just need to be in the poetry anthologies you find in a library – they can be in the incidental and accidental work your children create. One child did not realize he had repeated his words, but as he went to cross them out Kristi pointed out that some writers do that on purpose. Another child tried talking to the object in her poem, after the class sang, “You Are My Sunshine.” Both of these were cemented and celebrated in the week’s teaching. Rather than introduce a million different “tricks” the class is now trying these three, or selecting among these options to make a poem more powerful. It is not always the next thing that children need, sometimes it is just this thing – but better.

Finally, a few children carried over construction (as in book construction) work from previous units. The tape, staplers, and post-its all made a reappearance. Kristi constructed a chart to show children when they might choose one option over another. When you have one poem that is very long – you might tape it together. When you have a group of poems that go together (the example has one poem about each family member) you might staple them into a book. This work may seem obvious, but it is not. It asks children to consider: What goes together? What am I creating? These are big questions for little writers.

Let us know some ways you are using charts to support your young poets.

Until next time, happy Poetry Month and happy charting!

Kristi and Marjorie

Charting Poetry

Posted: April 8, 2013 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: charts, close reading, poetry, word choice 3 CommentsApril is Poetry Month and poems are everywhere – on the web, in classrooms, in subways, and in pockets. Teachers are teaching how to read poems and how to write poems. And they are making charts to capture it all. This week we highlight how charts can be used to capture our lessons, provide examples, offer strategies, and create challenges to strive towards.

Immersion Into Poetry

Charts capture our teaching and provide helpful reminders for our students in the way of tips and examples. How this might look in poetry is really no different than any unit where we begin with immersion into the genre or form we plan on reading and writing. Every poet will tell you that in order to write poems, you need to read poems – lots of poems. Poems of all shapes and sizes. Poetry is meant to be seen, heard and felt.

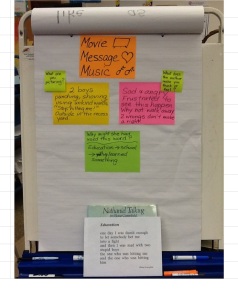

The chart below was built with some second grade students at Glenwood Landing Elementary School in North Shore, Long Island who were learning how to read poems closely. Marjorie (inspired by Rachel Rothman, one of our colleagues at the Reading and Writing Project) introduced three lenses they would listen through: movie, message, and music. When thinking which kind of visual supports would be most helpful, Marjorie decided to use examples generated by the students themselves. What she prepared ahead of time were the three prompts written out, enlarged copies of the poems (in this case two poems from Nathaniel Talking by Eloise Greenfield – “Education” and “When I Misbehave”) and some blank, large sticky notes.

Each reading of the poem was prompted by one of the lenses. This let the children know what to pay attention to as they listened. Then the children turned and talked to their partner, and came back together to share out what they had talked about. Examples of the children’s visualizations, feelings, and thinking were written down. This became an exemplar chart the children could use as a model when they went off and tried this on their own with another poem, “When I Misbehave” and any time thereafter, whenever they read a poem. The children actively listened and excitedly shared their thinking and ideas with each other and couldn’t wait to go off and do it again on their own.

The heading was pre-made, as were the prompts. The writing was generated by the students and their conversations.

Starting to Write Poetry

As with any writing unit, learning to generate topics is always one of the starting points and poetry is no different. A repertoire chart can capture possible options when reaching for something to write a poem about. The brilliant poet, Georgia Heard, offered many possibilities for poets and teachers alike in her book, Awakening the Heart, where she suggested that poets found topics by entering different doorways, such as the observation door, the heart door, the wondering door, and the concerns about the world door (as a start). The chart below is an example of a repertoire chart used in a first grade classroom at PS 192 in Brooklyn. First, Marjorie knew that kids love looking for things that hide, so used that idea

to create a heading that would grab the students’ attention and lead them on a search to find ideas for poems. Then she started by presenting a repertoire of strategies for generating poems: looking closely, feeling strongly, and things we wonder about. The idea of starting with a few options is important since not any one strategy will work on any given day.

Word Choice

One of the most delightful aspects of poetry is word play. Poets use words in delightful and unexpected ways. The more words you know the more options available to you. Words are a poet’s paintbrush that create images as vivid as a painting or photograph. Creating a chart that collects and sorts words poets can use can be a most useful tool. The following chart was launched by Marjorie in a second grade classroom at PS 192 in Brooklyn, but will grow and expand as kids find and discover more and more examples of specific nouns, vivid verbs, and descriptive adjectives. The thing to note is that each category is color-coded so when kids discover other examples they will write them on the colored index card that matches the category.

Another aspect of word choice is how words are used to compare one thing to another, called similes and metaphors. Similes help children go beyond literal observations towards adding in their imaginations and connections. It comes from the latin word “similis” to mean “like.” This might explain the misspellings on the chart. The word should be spelled “simile” not “similie.”

The teacher had previously defined what a simile was by giving some examples. The lesson Marjorie taught was designed to help children understand the many ways they could come up with similes by using their senses. Each post-it is a reminder of just how to do this. The visuals are familiar icons from earlier lessons when the senses were used to describe and elaborate writing.

Poetry offers so many opportunities to get excited about language, structure, and process. Another possible chart to create might highlight revision and all the possible ways a poet might revise a poem: changing words, layout, repetition, additional stanzas, or taking away unnecessary words.

Charts can be used to help students reflect and make goals based on what they have tried or not tried, or to create a rubric. This final example shows how this end of unit reflection happened in one first grade CTT classroom at PS 176 in Brooklyn. The children were taught to ask themselves two key questions, “What have I learned about writing poems?” and “What do I still need to work on?” They used a checklist to help with these questions by tallying each time they had used a particular strategy on the checklist. The strategy they had used the most was the one they were then expected to teach others.

These questions ask children to reflect on what they have accomplished and what they still need to work on.

The checklist included the things the teacher had taught during the poetry unit of study. They included “I used my senses,” “I used comparisons,” “I used repetition,” “I used special words,” and “I used white space.” Examples of each of these were included to the left of the checklist. In other words, this was a miniature version of the strategy chart created during this unit. Charts, as always, are only as effective as they are used.

Until next time, happy charting!

Marjorie and Kristi