Charting Poetry

Posted: April 8, 2013 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: charts, close reading, poetry, word choice 3 CommentsApril is Poetry Month and poems are everywhere – on the web, in classrooms, in subways, and in pockets. Teachers are teaching how to read poems and how to write poems. And they are making charts to capture it all. This week we highlight how charts can be used to capture our lessons, provide examples, offer strategies, and create challenges to strive towards.

Immersion Into Poetry

Charts capture our teaching and provide helpful reminders for our students in the way of tips and examples. How this might look in poetry is really no different than any unit where we begin with immersion into the genre or form we plan on reading and writing. Every poet will tell you that in order to write poems, you need to read poems – lots of poems. Poems of all shapes and sizes. Poetry is meant to be seen, heard and felt.

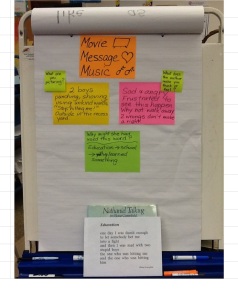

The chart below was built with some second grade students at Glenwood Landing Elementary School in North Shore, Long Island who were learning how to read poems closely. Marjorie (inspired by Rachel Rothman, one of our colleagues at the Reading and Writing Project) introduced three lenses they would listen through: movie, message, and music. When thinking which kind of visual supports would be most helpful, Marjorie decided to use examples generated by the students themselves. What she prepared ahead of time were the three prompts written out, enlarged copies of the poems (in this case two poems from Nathaniel Talking by Eloise Greenfield – “Education” and “When I Misbehave”) and some blank, large sticky notes.

Each reading of the poem was prompted by one of the lenses. This let the children know what to pay attention to as they listened. Then the children turned and talked to their partner, and came back together to share out what they had talked about. Examples of the children’s visualizations, feelings, and thinking were written down. This became an exemplar chart the children could use as a model when they went off and tried this on their own with another poem, “When I Misbehave” and any time thereafter, whenever they read a poem. The children actively listened and excitedly shared their thinking and ideas with each other and couldn’t wait to go off and do it again on their own.

The heading was pre-made, as were the prompts. The writing was generated by the students and their conversations.

Starting to Write Poetry

As with any writing unit, learning to generate topics is always one of the starting points and poetry is no different. A repertoire chart can capture possible options when reaching for something to write a poem about. The brilliant poet, Georgia Heard, offered many possibilities for poets and teachers alike in her book, Awakening the Heart, where she suggested that poets found topics by entering different doorways, such as the observation door, the heart door, the wondering door, and the concerns about the world door (as a start). The chart below is an example of a repertoire chart used in a first grade classroom at PS 192 in Brooklyn. First, Marjorie knew that kids love looking for things that hide, so used that idea

to create a heading that would grab the students’ attention and lead them on a search to find ideas for poems. Then she started by presenting a repertoire of strategies for generating poems: looking closely, feeling strongly, and things we wonder about. The idea of starting with a few options is important since not any one strategy will work on any given day.

Word Choice

One of the most delightful aspects of poetry is word play. Poets use words in delightful and unexpected ways. The more words you know the more options available to you. Words are a poet’s paintbrush that create images as vivid as a painting or photograph. Creating a chart that collects and sorts words poets can use can be a most useful tool. The following chart was launched by Marjorie in a second grade classroom at PS 192 in Brooklyn, but will grow and expand as kids find and discover more and more examples of specific nouns, vivid verbs, and descriptive adjectives. The thing to note is that each category is color-coded so when kids discover other examples they will write them on the colored index card that matches the category.

Another aspect of word choice is how words are used to compare one thing to another, called similes and metaphors. Similes help children go beyond literal observations towards adding in their imaginations and connections. It comes from the latin word “similis” to mean “like.” This might explain the misspellings on the chart. The word should be spelled “simile” not “similie.”

The teacher had previously defined what a simile was by giving some examples. The lesson Marjorie taught was designed to help children understand the many ways they could come up with similes by using their senses. Each post-it is a reminder of just how to do this. The visuals are familiar icons from earlier lessons when the senses were used to describe and elaborate writing.

Poetry offers so many opportunities to get excited about language, structure, and process. Another possible chart to create might highlight revision and all the possible ways a poet might revise a poem: changing words, layout, repetition, additional stanzas, or taking away unnecessary words.

Charts can be used to help students reflect and make goals based on what they have tried or not tried, or to create a rubric. This final example shows how this end of unit reflection happened in one first grade CTT classroom at PS 176 in Brooklyn. The children were taught to ask themselves two key questions, “What have I learned about writing poems?” and “What do I still need to work on?” They used a checklist to help with these questions by tallying each time they had used a particular strategy on the checklist. The strategy they had used the most was the one they were then expected to teach others.

These questions ask children to reflect on what they have accomplished and what they still need to work on.

The checklist included the things the teacher had taught during the poetry unit of study. They included “I used my senses,” “I used comparisons,” “I used repetition,” “I used special words,” and “I used white space.” Examples of each of these were included to the left of the checklist. In other words, this was a miniature version of the strategy chart created during this unit. Charts, as always, are only as effective as they are used.

Until next time, happy charting!

Marjorie and Kristi

Heya! I realize this is kind of off-topic however I had to ask.

Does building a well-established website such as yours take a lot of work?

I’m brand new to operating a blog however I do write in my diary everyday. I’d like to start a blog

so I can easily share my own experience and thoughts online.

Please let me know if you have any kind of recommendations or tips for brand new aspiring bloggers.

Thankyou!

Not off topic at all. Building a website is fairly easy, but it takes time and diligence to make it grow. We suggest connecting to social networks such as Facebook, Twitter, and Pinterest to connect with friends, colleagues and other educators.

[…] Charting Poetry […]